Three Waters Mountain, Wyoming

|

This is a special mountain: at its summit converge three major watersheds. Every year during the late spring or early summer, a pile of snow at a certain place on this mountain melts into three distinct basins. When water from one basin finally reaches the ocean, it will be well over a thousand miles distant from the mouths of the other two basins. There are only five places in the continental US that can make this claim -- one of the others is Headwaters Hill.)

|

|

|

I am fortunate to have three friends who are always eager for an adventure. In June 2006, we decided to climb Three Waters Mountain (or "3WM", as I'll refer to it). Here we are at our trailhead at Gunsight Pass. This was looking southeast; some other peaks in the northern Wind River Range can be seen in the distance:

|

|

We packed in a couple miles to a decent campsite near a small stream above an unnamed lake. After setting up camp, we hiked down to the lake, where we watched two elk take a swim. The place was infested with mosquitos -- I don't think I have ever seen them so thick. But we did have a striking view of the Teton Range, way off to the west:

|

|

The next morning we were eager to get moving -- the mosquitos weren't so bad once you got out of the trees and into the wind. This photo was taken looking back towards our campsite, from about halfway up to 3WM:

|

Those patches of snow were lying on the north face of Pinon Ridge. Meltwater eventually trickles into Fish Creek, which is a tributary of the Gros Ventre River, which flows into the Snake River, which in turn flows into the Columbia River, which enters the Pacific Ocean near Astoria OR. The far side of Pinon Ridge, however, drains into the Roaring Fork, which flows into the Green River, then the Colorado River, which empties into the Gulf of California, which meets the Pacific Ocean way down somewhere between Mazatlan and Cabo San Lucas, Mexico -- some 2000 miles down the coast from Astoria.

|

|

At far right, just underneath the snow, a small patch of trees is visible. Our campsite was not far from there, just off the edge of the photo. There are no trails in this area, but my general idea was to get to the top of Pinon Ridge, and then follow that crestline all the way up to the Continental Divide. So we ascended Pinon diagonally (underneath the large snowfield), and reached its crest near the far left side of that photo. Turns out it was unnecessary to do that so soon into the hike, though, because we ended up having to drop back down a bit into a small saddle. There we found a small pond and more elk. We then skirted the south side of unnamed point 10,862'. Not far beyond that, we crossed back over to the north side of the Pinon Ridge crest -- the photo above was taken from somewhere in that area. Further on, we had to cross numerous snowfields...

|

|

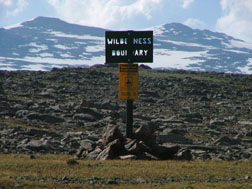

...but the weather was just right for hiking. As one approaches the "summit" of 3WM, it gets very flat, and it becomes difficult to know exactly where the "crest" of Pinon Ridge is. (3WM is at least two miles long, and the point marking the triple divide is not the same as the highest point on the mountain.) The USGS topo shows the ridge gradually bending to the south, so we kept going, and after awhile we came to the sign shown here:

|

|

It read "Wilderness Boundary", and it was encouraging, because according to my topo, the north edge of the Bridger Wilderness is defined as the crestline of Pinon Ridge. So from there we turned east (left), and it was not long before we saw a stake marking the triple divide. It is visible in this photo... barely. This gives some sense of the breathtaking dropoff to the east of 3WM. The snowfields visible there will melt into the third major watershed that is common to this point: Jakeys Fork finds its way into the Wind River, which becomes the Big Horn River, which is a tributary of the Yellowstone River, which flows into the Missouri River, which joins the Mississippi River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico south of New Orleans. Water heading that direction from here does so rapidly: it's about an 800-foot nearly-vertical drop, and then another 800 feet down to the valley floor:

|

|

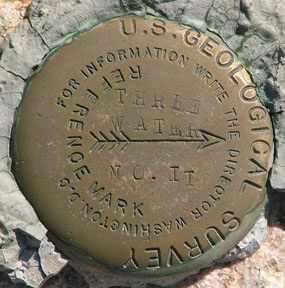

The mountains on the horizon are part of the Absaroka Range, at least 25 miles distant (that ridge is also part of the Continental Divide). The ridge in the middleground is about a half-mile to the north, but it is still a part of 3WM. In the foreground is visible the crumbling cairn that someone set up, although I'm not certain why that particular spot was chosen. By my reckoning, it was about 30 yards north of the actual triple divide (when I took the photo above, I was standing on what I figured was the actual point where the three watersheds converge). I will quickly concede, though, that it was very difficult to discern: as I've said, the summit is flat, and it is also completely strewn with boulders. Anyway, in the middle of the cairn was a weathered stake -- at one point it had been supported with guy wires, but those had long since failed (I imagine the weather's pretty nasty up there for most of the year). Not far from that cairn is the benchmark shown here:

|

|

To me that implies that there should be another marker in the direction of the arrow, but I never did find one (maybe it was under the cairn). Soon it was time to head back down to "Mosquitoville" (as one my friends had christened our campsite). We had planned on staying there another night, but with our goal having been accomplished, we decided there was no good reason to put up with the bugs any longer, so we packed out. This photo was looking west across Gunsight Pass, which is a low spot on Pinon Ridge. To the left is Bridger National Forest and the Colorado River watershed, while to the right is Teton N.F. and the Columbia watershed:

|

At the time of our visit, the top of that ridge was as far as we could legally go in a motor vehicle. Some visitors before us had clearly not been pleased with that ruling: the fence blocking the way was pretty much destroyed, and the sign had been yanked out and tossed down the hillside. I point this out so that -- if you are thinking about going -- you can spare yourself the mistake of driving down into the Gunsight, like we did. We were about halfway down the slope when I noticed the sign -- lying facedown -- and by that point, we had no choice but to continue the rest of the way down and turn around. We barely had enough horsepower to get back up to the top of the ridge.

Research and/or photo credits: Dale Sanderson

Page originally created 2007;

last updated Nov. 17, 2016.

last updated Nov. 17, 2016.