The Washington Meridian (or, "the American Meridian")

|

During a relatively brief period beginning in 1850, the "prime meridian" in the United States was not "the Prime Meridian" (i.e. the Greenwich Meridian), but rather the "American Meridian" (also known as the "Washington Meridian").

|

|

This meridian was defined as passing through the center of the original dome atop the main building of the Naval Observatory in Washington, DC (the old Naval Observatory, that is, not the current one). Despite the fact that the U.S. used this meridian for only a few decades, it was during this timeframe that the boundaries of several western states were established. Included among these were both the eastern border of Colorado (defined as 25 degrees west of Washington), and the west boundary (32 degrees west of Washington).

It is interesting to note that there were actually a total of four "prime meridians" used by the U.S. prior to its 1912 adoption of the Greenwich Meridian. The original American Meridian passed through "the Congress House" (today's Capitol building). A later meridian was defined as passing through "the President's House", now known as the White House. (Several other features are also located on this meridian, the most conspicuous of which are the Jefferson Memorial and 16th Street NW.) The third American Meridian was through the old Naval Observatory, as described above (24th Street NW lies along this meridian). The Naval Observatory moved to its present location on Massachusetts Avenue in 1893, prompting the fourth meridian, which passed through the clock room: a small building located at the center of the 1000-foot radius of the observatory grounds. After the Naval Observatory was moved, the original facility has housed various other Naval departments*. Currently the "Observatory Hill" complex (as it is sometimes referred to nowadays) is home to the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (or Bu-Med for short). Of these four American Meridians, it appears that only the third (the one through the old Naval Observatory) was ever used in defining any state boundaries.

|

Over the years I have made some effort to visit each of Colorado's corners, and along the way I have gleaned a bit about how the state's boundaries were defined and surveyed. So as I was preparing for a summer 2009 family trip to Washington DC, one of the places I was interested in visiting was the old Naval Observatory, since the boundaries of my state are defined in relation to this building. However, I soon learned that Bu-Med is unfortunately not open to the public**. Too bad... but I did receive something of a consolation prize: as my family was walking from the Arlington Cemetery to the Lincoln Memorial, I caught sight of a small white observatory dome off to the north. Conscious of what I was looking at, I took this photo...

|

|

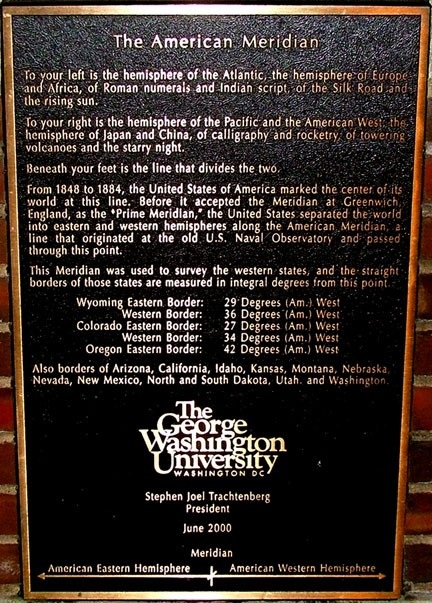

...and then, right there on the Arlington Bridge, I proceeded to give my family a brief lecture on the relationship of that building to the shape of our own state, hundreds of miles off beyond the western horizon. (Alas, it was received with rolling eyeballs and much less interest than I would've hoped.) Later on that same trip, we visited the American Meridian plaque, at the southeast corner of 24th and "H" streets:

|

I have a few problems with the text of that plaque, foremost of which is the fact that all of the specified lines of longitude appear to be off by two degrees! Wyoming's east and west lines are actually 27 and 34 degrees, respectively; while Colorado's are 25 and 32 degrees. And I'm not sure Oregon's eastern border was really defined according to this meridian. In fact, I don't think any of California's or Washington's borders have anything to do with this meridian, either.

|

|

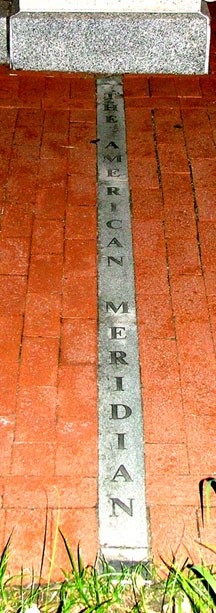

On the sidewalk at the foot of that marker, a granite strip is inlaid among the bricks, engraved with the text "The American Meridian":

|

The design of this small monument can lead one to believe that they are standing right on the actual meridian, but from what I observe on aerial photos, I am skeptical that is truly the case. Rather, it appears 24th St sits on the actual meridian. (Or, probably more accurately, the observatory was built upon the centerline of 24th Street's right-of-way, and thus 24th became the de facto meridian). Of course it wouldn't have been practical to put a marker in the middle of the street, so I imagine this site along the sidewalk was deemed to be close enough. But it has given rise to some dubious claims. For example, it has been stated that this Meridian bisects some of the buildings on the George Washington University campus. Well, 24th Street doesn't run through any buildings, so I don't think the Meridian does, either. I suspect these misconceptions can be traced back to the placement and design of this monument, and the way things are worded on the plaque.

Anyone who has had elementary-level geography should be familiar with the concept of the Prime Meridian, but it would seem far fewer people are aware of the fact that the U.S. once had a different "prime meridian" of its own. As we've seen, the position of this meridian was determined by the location of an observatory. Or, to put it another way, the meridian was not defined in relation to a whole-integer degree of longitude west of Greenwich. The American Meridian was about three arc-minutes away from 77 degrees west of Greenwich, which translates to nearly three miles. Chandler Robbins, the man who led the survey team that set the original Four Corners monument, anticipated the confusion that this offset might cause, so in a letter to the Santa Fe newspaper, he wrote the following about the west boundary of Colorado: "It seems to have been the general impression that the line was the 109 degrees of longitude west of Greenwich. Such is not the case, as the law makes it 32 degrees of longitude west from Washington, which corresponds to 109 degrees 02 minutes 59.25 seconds west from Greenwich, and which places the line a small fraction less than three miles farther west than would have been the case if it had been run as the 109 degrees of longitude." That letter was written way back in 1875. We have had plenty of time to absorb the facts. But every now and then someone notices that the Colorado/Utah stateline is not exactly on the 109th Meridian west of Greenwich. Sometimes someone in the news media latches on to this fact, and sometimes they fail to fully research the issue before announcing to their audience something along the lines of "The Four Corners Monument is off by 2.5 miles!" Claims like that are patently untrue. For one thing, the location of Four Corners (and several other state boundaries) was not defined in terms of the Greenwich Meridian -- it was never intended to be located at 109 degrees west of Greenwich. Secondly, even if a boundary monument is not located exactly where it ought to have been (which is true in just about every case, to a greater or lesser extent), once the boundary as surveyed has been accepted by the relevant jurisdictions, that becomes the legal boundary... regardless of any future claims of inaccuracy. |

References and links

National Geodetic Survey

Twelve Mile Circle blog

Wikipedia

George Washington University Libraries

Footnotes

*A concise history of the grounds of the old observatory

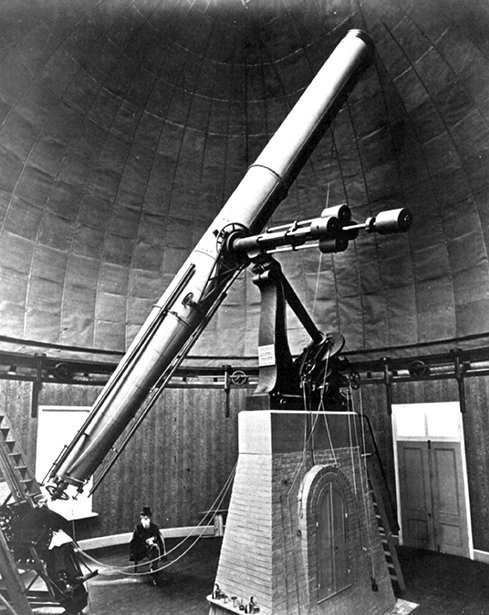

**Bu-Med was not closed to the public back in 1972, when a gentleman by the name of Leonard Abbey wanted to visit the observatory (although for a different reason than mine). I am grateful that he posted his recollection on the web, not only because it is interesting to note how the usage of these buildings has changed over the years, but also because it helped me to determine that it was the original (smaller) dome that was in use when western states were being defined, not the second (larger) dome, which has since been replaced with a more conical roof. It was with a telescope under this larger dome in 1877 that Asaph Hall discovered the natural satellites of Mars. But that telescope was not built until 1875, so I think it is safe to assume that during the 1860s (when Congress was defining the boundaries of twelve western states and territories), only the one smaller dome was extant at the old Naval Observatory. Lenny's was a well-written and fascinating page, but he passed away in 2012, and as of 2014 his former web domain was owned by a completely unrelated organization. Fortunately his article was also available elsewhere, in an issue of the Atlanta Astronomy Club's newsletter. I have taken the liberty of copying the text and preserving it below, in order to assure its continued accessibility.

National Geodetic Survey

Twelve Mile Circle blog

Wikipedia

George Washington University Libraries

Footnotes

*A concise history of the grounds of the old observatory

**Bu-Med was not closed to the public back in 1972, when a gentleman by the name of Leonard Abbey wanted to visit the observatory (although for a different reason than mine). I am grateful that he posted his recollection on the web, not only because it is interesting to note how the usage of these buildings has changed over the years, but also because it helped me to determine that it was the original (smaller) dome that was in use when western states were being defined, not the second (larger) dome, which has since been replaced with a more conical roof. It was with a telescope under this larger dome in 1877 that Asaph Hall discovered the natural satellites of Mars. But that telescope was not built until 1875, so I think it is safe to assume that during the 1860s (when Congress was defining the boundaries of twelve western states and territories), only the one smaller dome was extant at the old Naval Observatory. Lenny's was a well-written and fascinating page, but he passed away in 2012, and as of 2014 his former web domain was owned by a completely unrelated organization. Fortunately his article was also available elsewhere, in an issue of the Atlanta Astronomy Club's newsletter. I have taken the liberty of copying the text and preserving it below, in order to assure its continued accessibility.

The Washington Refractor

by Lenny Abbey, c. 1972

Anyone who has studied history in high school or college knows that a text book is a poor source of education. The images conjured up by even the most skillful of writers are at best fleeting. You are lucky to remember them until exam time. On the other hand, experience is a powerful teacher. An actual visit to the scene of a great event enables you to take home a memory which will live for years. The sites of many historical events have been preserved for our education and enjoyment. The scenes of other historical events, perhaps of less interest to our teachers, have been forgotten, and put to other uses. Finding these places, many of which may be of importance to you, even if not to the general population, can be a rewarding experience.

On a 1972 trip to Washington, D.C., I decided to visit the original location of the Naval Observatory’s 26" refractor, where Asaph Hall discovered the satellites of Mars in 1877. The 26" refractor was at the time the largest refracting telescope in the world. It was Alvan Clark’s first really large instrument, and it was this telescope that catapulted the Clarks to fame. Though the big refractor now enjoys a modern mounting on the outskirts of Washington, it was originally located in a building in town, “near the river and the Navy Yard”, as one history book put it. That was our only clue.

Before departing for the nation’s capital, a long-distance phone call was made to Bob Wright, President of the Astronomical League, and long a resident of the D.C. area. He said that he would be out of town while we were there, but would find out what he could about the old observatory.

We arrived on a very rainy day. Bob Wright had left a message that the original Naval Observatory, now called “The Old Transit House”, was part of the present Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, near the Lincoln Memorial. Calling the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, we were told that no one there was really sure which telescope had actually been located on the grounds. Now a “Transit House” surely does not suggest a very large refractor, and besides, the Lincoln Memorial is nowhere near the Navy Yard. We decided to gamble on a visit to the Navy Yard.

A quick call to the Pentagon – if you have ever called the Pentagon, you know how funny that is – resulted, after a number of transfers, in a conversation with the Navy’s Public Information Office. They said that there were many old buildings in the Yard, but nobody was very familiar with their history. He recalled that there was an old employee there who had at one time made a study of the Yard’s history, but he was now dead or retired; no one was sure which.

At this point the explorer within us rebelled, and we decided to visit the Navy Yard in person to seek out the hallowed spot. After all, who was better qualified to recognize an ex-observatory? After a meandering, error-ridden journey through parts of Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, we finally located the Yard. A quick drive through revealed no observatory, but we did find the Navy Yard Museum. Picking our way through assorted cannon, anchors, and capstans, we found our way to the office of the Curator. Yes, he had heard of the old Naval Observatory. After rummaging through several old filing cabinets, he announced that it was located at – care to guess? – the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

It was now 4:00 p.m., dangerously close to quitting time. The rain was heavier than ever, but a mad dash across town brought us to our goal in record time. Success was near! “Bu Med”, as the Curator had called it, was located on the top of a modest hill. This was a good sign. When we had found the main building, we asked for the Public Information Office, and were ushered into the office of the Assistant Surgeon General, who doubled in this capacity. This, he told us, was indeed the site of the original Naval Observatory. The building next door had once housed the Great Refractor. Looking out his window, we saw our goal: a shining silver dome atop a rather large building.

The building is now used for office space. Even though the dome still sits regally above the roof, the observing room beneath it is now used as a reception room for several offices. No trace of the telescope’s old pier remains. The wheels have been removed from the dome, and it is bolted in place. A number of large pictures about the room commemorate the telescope and that famous night ninety-five years ago.

Anyone who has studied history in high school or college knows that a text book is a poor source of education. The images conjured up by even the most skillful of writers are at best fleeting. You are lucky to remember them until exam time. On the other hand, experience is a powerful teacher. An actual visit to the scene of a great event enables you to take home a memory which will live for years. The sites of many historical events have been preserved for our education and enjoyment. The scenes of other historical events, perhaps of less interest to our teachers, have been forgotten, and put to other uses. Finding these places, many of which may be of importance to you, even if not to the general population, can be a rewarding experience.

On a 1972 trip to Washington, D.C., I decided to visit the original location of the Naval Observatory’s 26" refractor, where Asaph Hall discovered the satellites of Mars in 1877. The 26" refractor was at the time the largest refracting telescope in the world. It was Alvan Clark’s first really large instrument, and it was this telescope that catapulted the Clarks to fame. Though the big refractor now enjoys a modern mounting on the outskirts of Washington, it was originally located in a building in town, “near the river and the Navy Yard”, as one history book put it. That was our only clue.

Before departing for the nation’s capital, a long-distance phone call was made to Bob Wright, President of the Astronomical League, and long a resident of the D.C. area. He said that he would be out of town while we were there, but would find out what he could about the old observatory.

We arrived on a very rainy day. Bob Wright had left a message that the original Naval Observatory, now called “The Old Transit House”, was part of the present Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, near the Lincoln Memorial. Calling the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, we were told that no one there was really sure which telescope had actually been located on the grounds. Now a “Transit House” surely does not suggest a very large refractor, and besides, the Lincoln Memorial is nowhere near the Navy Yard. We decided to gamble on a visit to the Navy Yard.

A quick call to the Pentagon – if you have ever called the Pentagon, you know how funny that is – resulted, after a number of transfers, in a conversation with the Navy’s Public Information Office. They said that there were many old buildings in the Yard, but nobody was very familiar with their history. He recalled that there was an old employee there who had at one time made a study of the Yard’s history, but he was now dead or retired; no one was sure which.

At this point the explorer within us rebelled, and we decided to visit the Navy Yard in person to seek out the hallowed spot. After all, who was better qualified to recognize an ex-observatory? After a meandering, error-ridden journey through parts of Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, we finally located the Yard. A quick drive through revealed no observatory, but we did find the Navy Yard Museum. Picking our way through assorted cannon, anchors, and capstans, we found our way to the office of the Curator. Yes, he had heard of the old Naval Observatory. After rummaging through several old filing cabinets, he announced that it was located at – care to guess? – the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

It was now 4:00 p.m., dangerously close to quitting time. The rain was heavier than ever, but a mad dash across town brought us to our goal in record time. Success was near! “Bu Med”, as the Curator had called it, was located on the top of a modest hill. This was a good sign. When we had found the main building, we asked for the Public Information Office, and were ushered into the office of the Assistant Surgeon General, who doubled in this capacity. This, he told us, was indeed the site of the original Naval Observatory. The building next door had once housed the Great Refractor. Looking out his window, we saw our goal: a shining silver dome atop a rather large building.

The building is now used for office space. Even though the dome still sits regally above the roof, the observing room beneath it is now used as a reception room for several offices. No trace of the telescope’s old pier remains. The wheels have been removed from the dome, and it is bolted in place. A number of large pictures about the room commemorate the telescope and that famous night ninety-five years ago.

|

But something was wrong. A 26-inch, f/16 refractor would have a focal length of almost thirty-five feet. This room was a scant twenty-five feet in diameter. As the twenty-six inch was not part of the observatory’s original equipment, it was reasonable to assume that there had been another, smaller equatorial refractor which dated from its inception. (A later trip to the Smithsonian Institution revealed a 9.5-inch lens which had once belonged to the Naval Observatory. At f/16, this lens would have a focal length of 13-feet, fitting rather nicely into the Bureau of Medicine’s modest dome.)

Further investigation revealed a likely solution to the problem. Extending south from the small dome was a narrow room, about 100 feet long. This must have been the transit room, hence the name “Old Transit House”. The Washington Meridian, which was almost selected as the Prime Meridian, must have been defined by the instruments in this room. At the southern end of the transit room is a large circular room approximately 50 feet in diameter. This would in no way cramp the style of a 35-foot telescope tube. The room is at present topped by a conical roof, and it contains a large number of file cabinets; a necessarily inefficient use of a room specifically designed for another purpose. Conversation with the workers in this room revealed that they were totally unaware of its original use. There is no indication, by historical marker or photograph, that perhaps the most unusual objects in our solar system were discovered here. Asaph Hall and Alvan Clark have been gone for many years, but to stand on this spot is to remember their achievement, and to somehow share in their great discovery. It is an experience to be recommended to everyone. |

Research and/or photo credits: Dale Sanderson

Page originally created 2010;

last updated Nov. 17, 2016.

last updated Nov. 17, 2016.